How should we test this? Part 6 - Reporting

Part 6 in "How should we test this?" on reporting and getting feedback

This blog series explores a central question in software testing: “How should we test this?” (HSWTT?) We'll start with some foundational concepts that shape how we approach testing: learning, modelling, and heuristics. From there, the series dives into practical thinking tools: how to learn about the product (Product Analysis), how to identify important potential problems (Risk Analysis) and how to search for those problems effectively (Test Strategy). Finally, we’ll look at how to communicate what we’ve found in a meaningful way (Reporting).

How should we test this:

- Part 1 - Introduction

- Part 2 - Learning

- Part 3 - Product Analysis

- Part 4 - Risk Analysis

- Part 5 - Test Strategy

Part 6: Reporting

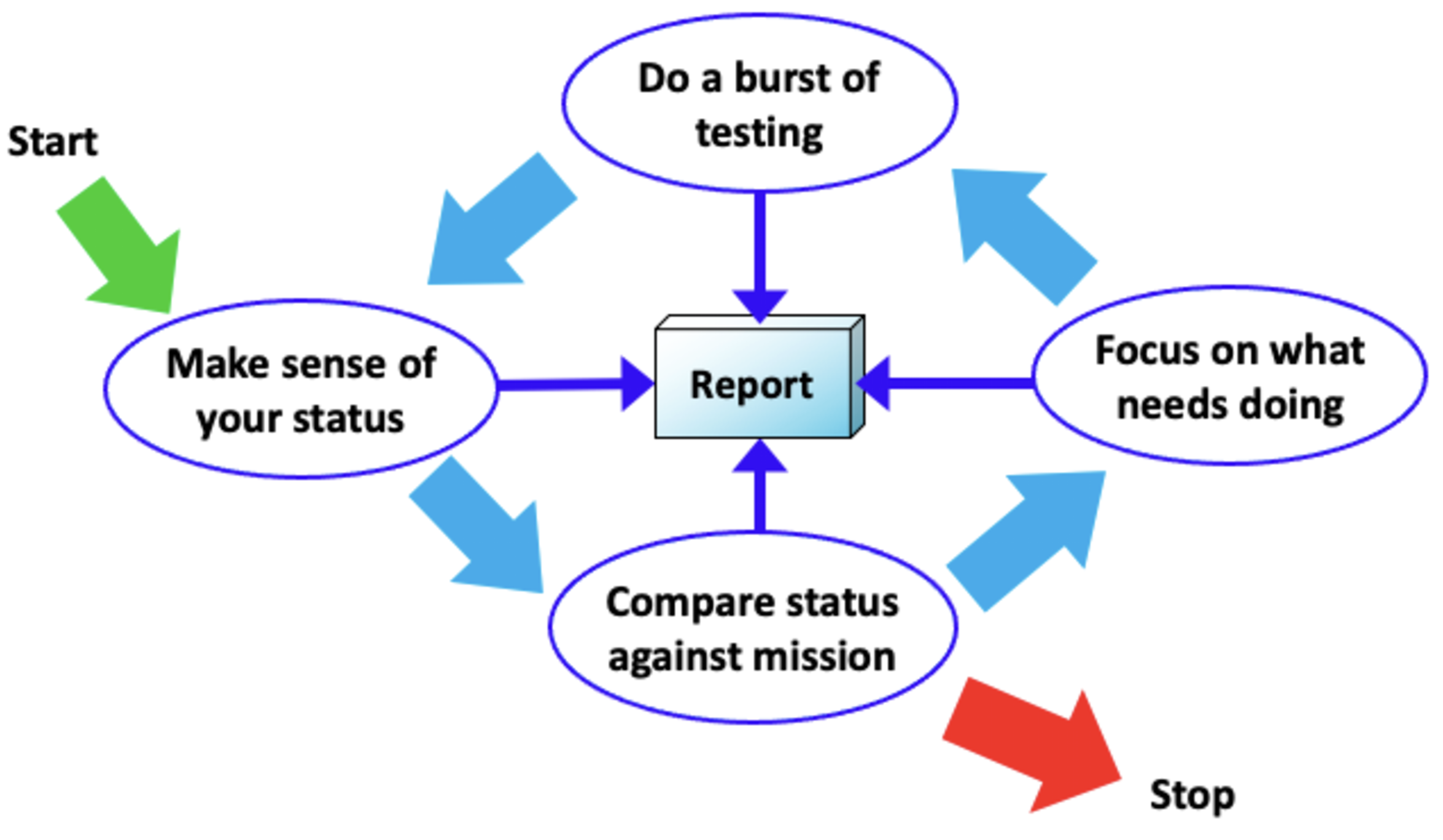

Reporting is an important concept to keep track of where you are. Creating insight in the important question “are there problems that threaten the on-time, successful completion of the product?” is an important job testers often do. With reporting I do not mean a written report. Reporting can be done verbally or even in your head when you defocus for a while and think of what you have done.

Many testers do not even report and the organisation assumes that if the checks are all green, testing is done and the product is okay… Most test reports I have seen are not very good either. They talk about the status of the testing instead of the status of the product! They lack all the important information stakeholder want from the testing. They are full of useless metrics like test cases and bug counts. Stakeholders want information about the status of the product, about test coverage and about remaining risks.

Coverage & Release Coverage Outlines

In Rapid Software Testing we define coverage as: “Coverage is how thoroughly you have examined the product with respect to some model”. So, code coverage is how thoroughly you have examined the product with respect to some model of the code. Code coverage is the only kind of coverage you can quantify because you can count lines of code and the lines which are covered by some sort of check. But how do you measure the interesting types of coverage:

- Product coverage: What aspects of the product did you look at?

- Risk coverage: What risks have you tested for?

- Requirements coverage: What requirements have you tested for?

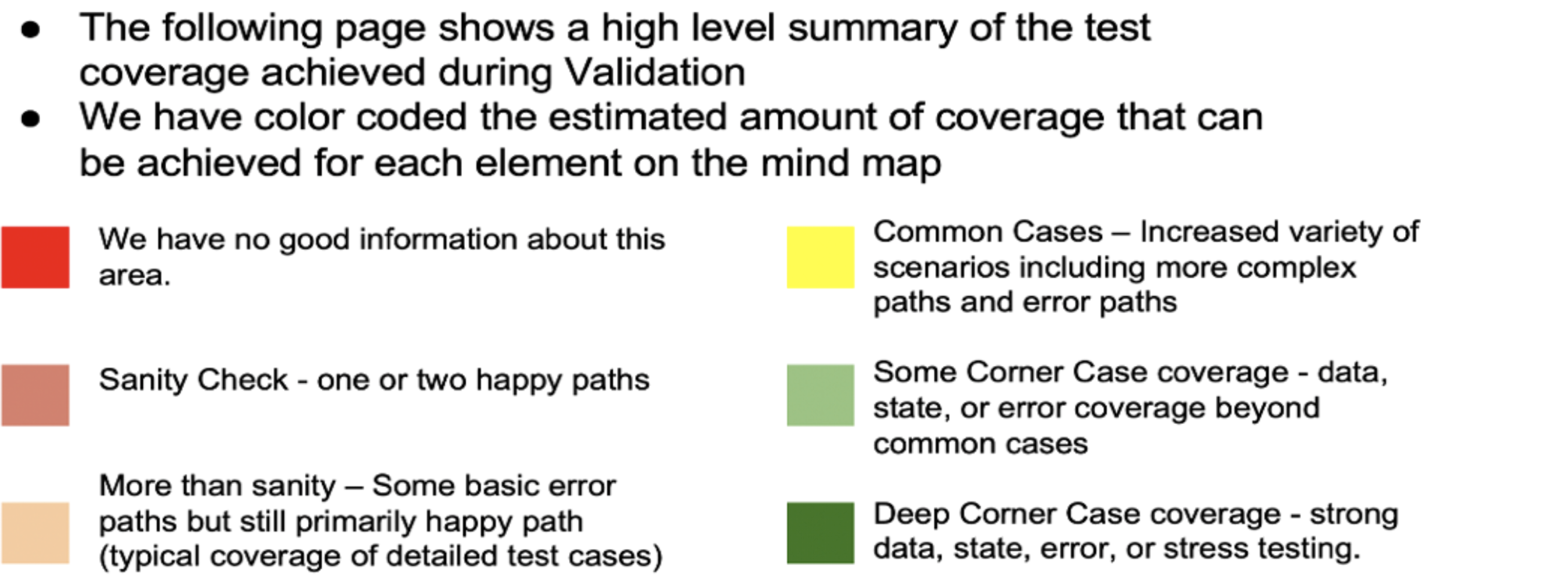

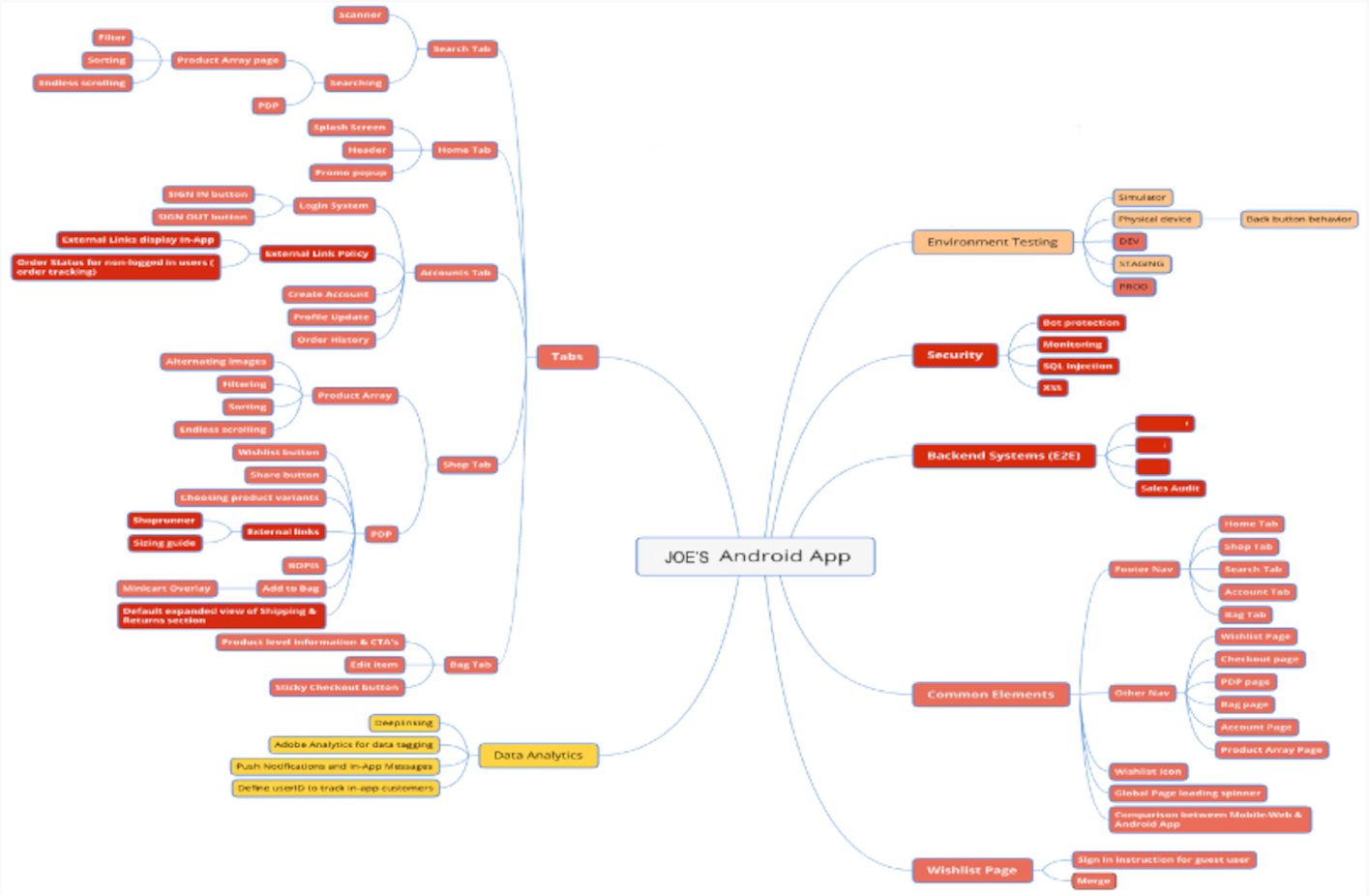

In many teams I see testers refer to their test cases and invite their customer to have a look at Jira or some other test cases management tool to see the coverage. Their report count test cases and describe bugs. To be able to report on these kinds of coverage, you’ll need a model of the product. Your Product Coverage Outline (PCO) can be used for this. Paul Holland worked with his teams an created this great example

Where you can see that this regression test of the App was done on two specific areas are tested with “more than sanity” and “common cases” where the rest of the app was sanity check or not tested at all. This mind map gives great insight in product coverage.

Paul Holland calls it Release Coverage Outlines (RCO). They are similar to Product COverage Outlines (PCO, more about PCO see part 3 - Product Analysis) but with less detail. Using a RCO stakeholders can quickly identify which parts of the product were tested with what intensity. RCOs can be also be used to present proposed test coverage before actual testing. This helps teams to discuss and determine the right and desired coverage.

To Report on Testing is to Tell a Story

In RST we define testing as to evaluate a product by learning about it through exploration and experimentation with so that you help your clients to make informed decisions about risk. We also talk about that testers see things for what they are. They make informed decisions about quality possible because they provide actionable information.

This actionable information is structured by the testing story. This story must make sense of the test process, test progress and results by rendering information into a compelling story for your stakeholders (which includes yourself). The testing story consists of three parts:

A story about the status of the PRODUCT The product story informs our clients how the product is doing: what works and what fails. Michael Bolton says: “It is a qualitative report about a product requires us to relate the nature of the product, the people who matter, and the presence or absence of value, risks, and problems for those people. Qualitative information makes it possible for our clients to make informed decisions about quality.”

A story about how you TESTED it The testing story gives warrant to the product story. The testing story is about the coverage we obtained and how we collected the information about the product.

A story about the VALUE of your testing The story about the quality of our testing tells our stakeholder how happy they should be with our testing, what risk have been mitigated and which risks are still open.

Stop talking about testing (only), talk about the product, risks, and value. Give your stakeholders a clear summary of the overall status of the project using words NOT metrics. Show product coverage using coverage outlines. Only highlight bugs that may impact the business and explain why. And finally, do not include meaningless counts of test cases but instead talk about effort (spend and remaining)

More on Reporting and storytelling:

- Braiding The Stories - Michael Bolton

- Breaking the test case addiction – Test reporting - Michael Bolton

- Let’s stop talking about testing, let’s start thinking about value - Alex Schladebeck & Huib Schoots

- The Science Behind the Art of Storytelling - Lani Peterson

Wrapping Up

when have we tested enough? To determine if a team has tested enough, is a social question. Do we as a team have enough confidence or trust in our work? Does de product owner have enough trust in the product? Unfortunately, there is no objective method or algorithm for answering this question.

Telling the testing story helps you (and your team and stakeholders) to decide if you have tested enough. There is more to it to be able to decide if you have tested good enough, if you have tested enough or you can stop testing.

How do you know that the product is good enough? That no major problems have been overlooked? Well, you never know. There is no way to be sure. But how do you decide that your team is in good shape?

- If you know enough about the product to judge it

- and you feel that the known problems are not serious enough

- and you think that there are (probably) no hidden remaining (serious) problems

- and you can explain why you know enough

- and your quality story is convincing.