How should we test this? Part 3 - Product Analysis

Part 3 in "How should we test this?" on Product Analysis and how to learn what the product actually is.

This blog series explores a central question in software testing: “How should we test this?” (HSWTT?) We'll start with some foundational concepts that shape how we approach testing: learning, modelling, and heuristics. From there, the series dives into practical thinking tools: how to learn about the product (Product Analysis), how to identify important potential problems (Risk Analysis) and how to search for those problems effectively (Test Strategy). Finally, we’ll look at how to communicate what we’ve found in a meaningful way (Reporting).

How should we test this:

Part 3: Product Analysis with a Product Coverage Outline

Before we start thinking about what to test and how to do it, it’s important to learn about the product we want to test. Learn about your mission or test assignment. Discuss what your stakeholders expect from you. What kind of information do they want from testing? What kind of decisions do they need to take using the information from testing? Also learn about the product.

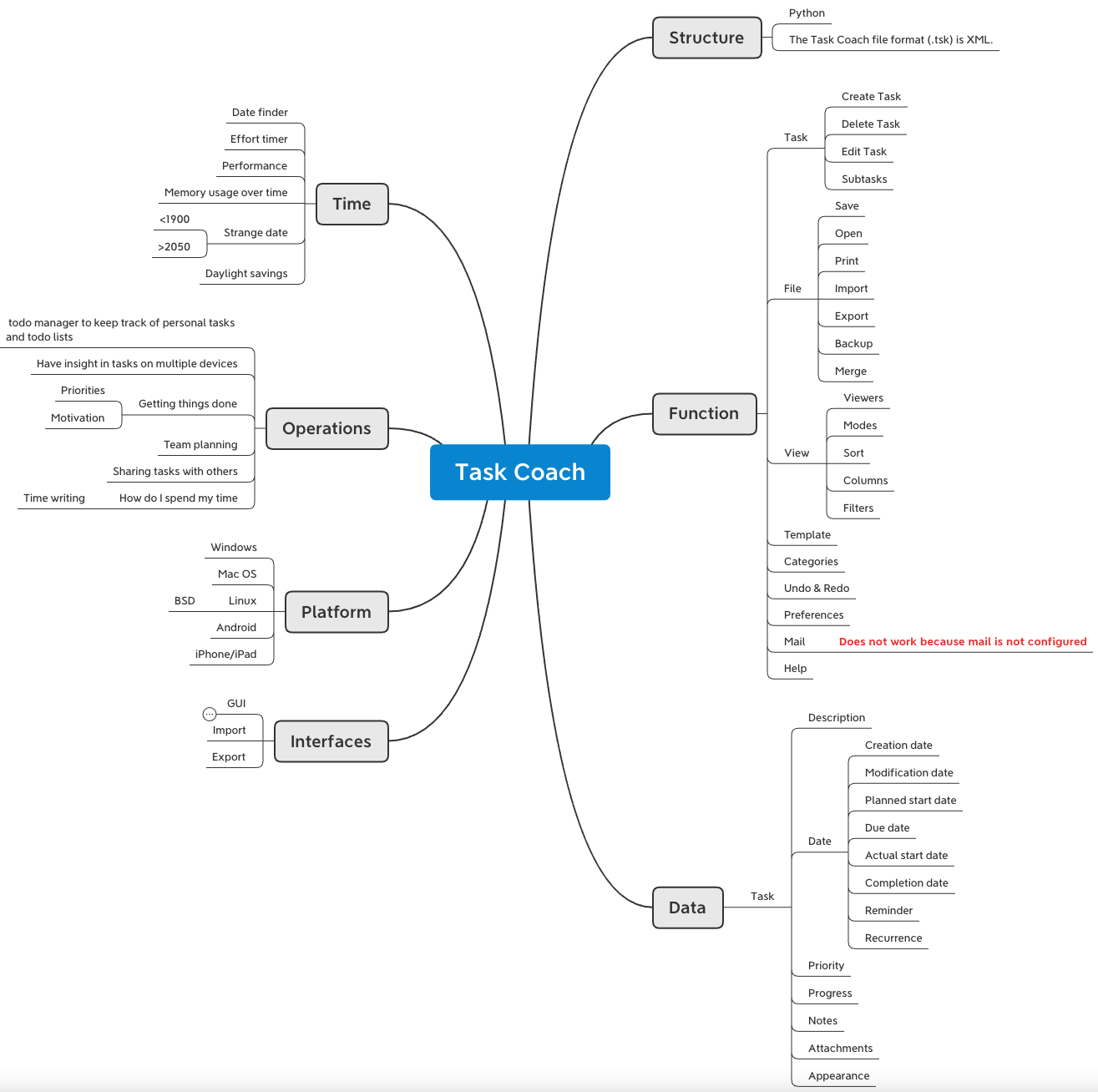

A product coverage outline (PCO) is a model of the product. Like a map of the world or a city. It can be described as a parts list or an inventory of elements listing the components of a product. Essentially it is a list of items of a product that could be interesting to test in some way.

Survey sessions and touring

How do you create a product coverage outline? While doing a survey session1 on the product, you map product factors that could matter. A product factor is something about the product that you might wish to cover in some test. Put these factors on the PCO if there is some chance you would otherwise forget or neglect them.

Consider touring of product2 and record what you see. Investigate every (sub) menu item, context specific items, text, check, and pop-up boxes, (radio) buttons and other visual elements like pictures, backgrounds, and logos. Talk with designers, stakeholders, businesspeople, customers, customer service, etc. Look at previous versions, marketing information and competing products. Read the specifications (although I try to learn and model the product on my own first before looking at the requirements).

San Francisco Depot

Software is complex and the biggest part is invisible. Take care to cover all of it that matters, not just the parts that are easy to see. You could consider using SFDIPOT (Product elements from the Heuristic Test Strategy Model) during the creation of a PCO. Products have many dimensions. Each category, listed below, represents an important and unique element to be considered. It includes things users see, and things they don’t see:

- What the product is (Structure)

- What the product does (Functions)

- The data it processes (Data)

- The interfaces that it provides or uses (Interfaces)

- Things it depends upon (Platform elements)

- Kinds of things users might do with the product (Operation)

- Relationships between the product and time (Time)

While creating a PCO you could also make notes of bugs you see, questions or concerns you have and start a risk list. I often add an extra “test” node and put this information temporarily in that separate node in my mind map. Later on risks will move to a separate mindmap or list.

Example PCO

Why do we do this? A PCO is a learning tool to gain deeper understanding of the product. It helps you examine and learn about the product from many different perspectives. The better we understand the product, the better we can design, build, and test it. By doing risk analysis we create more insight: by not only thinking in solutions, but also in problems. Discussing your work with others promotes diversity in thinking by using multiple perspectives. This facilitates deeper discussions and more insight in teams. By creating a PCO we create models and visualisations which are easy to discuss with the team, allowing the whole team to think along. Mapping also helps to structure your mental model of the complex product. A PCO helps doing risk analysis and creating a test strategy. Later you can use the PCO to map and visualize coverage. It might take some time to learn. Creating a PCO shouldn’t take a lot of time. On average it takes me 30-60 minutes. In the example below I have

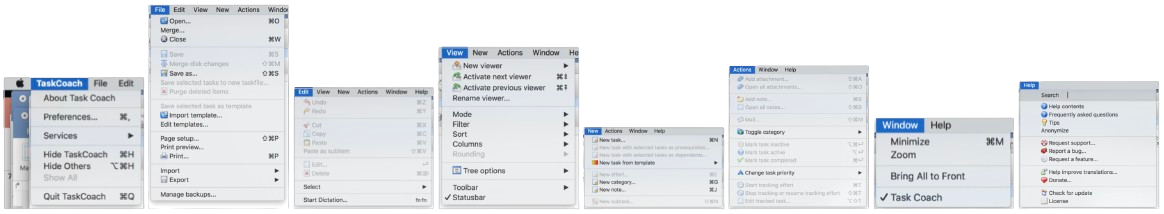

Another habit I find helpful is taking screenshots of the menu or key screens of the product I’m learning. It gives me a quick visual overview of what’s available and how things are structured.

Final notes

A PCO doesn’t have to be a mind map. Any other way is okay, as long as it helps you learn about the product and build a good (mental) model of what the product is. A PCO or any product model for that matter, can be made in many ways: a list, a table, a drawing or diagram, a mind map, etc. In the examples mentioned below shows many ways to make a PCO. Also note that a PCO doesn’t have to be in a SFDIPOT format. It is NOT a template, but a heuristic you can use to help you create a PCO.

More on Product Coverage Outlines:

Survey testing = any testing that has as its primary goal learning about the design, purposes, testability, and possibilities of the product. Survey testing tends to be open and playful. It provides a foundation for effective, efficient testing, later on. ↩︎

Touring = is a tactic where the tester explores and investigates a product like touring a city on holiday, using different aspects to guide and focus the investigation like structure, data or documentation. More on tours here ↩︎